Ocean Visions. (2025) Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal: Road Maps. https://www2.oceanvisions.org/roadmaps/ remove/mcdr/ Accessed [insert date].

Electrochemical CDR

State of Technology

State of Technology

Overview

Electrochemical carbon dioxide removal technologies utilize techniques that capture and remove dissolved inorganic carbon from seawater (either as CO2 gas or as calcium carbonate), and/or produce a CO2-reactive chemical base, e.g. sodium hydroxide (NaOH), that can be distributed in the surface ocean to ultimately consume atmospheric CO2 and convert it to long-lived, dissolved, alkaline bicarbonate. These techniques are sometimes called “direct ocean capture” to draw comparisons with direct air capture and encompass both electrodialytic and electrolytic processes.

In electrodialytic approaches, electricity provides the energy to rearrange the most common components of seawater, H2O and NaCl, into acidic (hydrochloric acid; HCl) and basic (sodium hydroxide; NaOH) solutions (House et al., 2007). The acidic solution can then be used to strip dissolved inorganic carbon from seawater in the form of gaseous CO2, or the basic solution can be used to strip the dissolved inorganic carbon by precipitating solid calcium carbonate (Note: Production of calcium carbonate via electrodialysis results in the basic component becoming acidified. This acidic stream may need to be neutralized through addition of a base before being recombined). In addition, the basic component can be selectively added to seawater to draw additional CO2 into the ocean to be stably stored as bicarbonate ions. Electrolytic approaches split water and salt into hydrogen and oxygen and/or chlorine gases, and produce alkaline metal hydroxide (e.g., sodium hydroxide) and acid as byproducts (Rau et al., 2018). When added to surface seawater, the hydroxide reacts with CO2 in seawater to form dissolved alkaline bicarbonate. The resulting CO2 undersaturation in surface seawater then forces atmospheric CO2 to enter the ocean and be stored largely as long-lived seawater bicarbonate.- House, Kurt Zenz, Christopher H. House, Daniel P. Schrag, and Michael J. Aziz. “Electrochemical Acceleration of Chemical Weathering as an Energetically Feasible Approach to Mitigating Anthropogenic Climate Change.” Environmental Science & Technology 41, no. 24 (December 2007): 8464–70. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0701816.

- Production of calcium carbonate via electrodialysis results in the basic component becoming acidified. This acidic stream may need to be neutralized through addition of a base before being recombined.

- Rau, G.H., Willauer, H.D. & Ren, Z.J. The global potential for converting renewable electricity to negative-CO2-emissions hydrogen. Nature Clim Change 8, 621–625 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0203-0

Technology Readiness

Electrodialytic approaches are already commercial technologies used in applications such as whey demineralization, organic acids recovery, and desalination, among others (Bazinet & Geoffroy, 2020).

The electrolytic production of H2, O2/Cl2, hydroxide, and acid is a very mature technology that globally produces some 75 Mt of NaOH per year that is an essential reagent in a variety of important industrial processes (e.g., in food processing, soap production, pulp and paper, pharmaceuticals, etc.) (Lakshmanan & Murugesan, 2014).

An electrolytic approach to precipitate calcium carbonate has recently been proposed (Callagon La Plante et al., 2021). This approach electrochemically generates alkalinity in order to precipitate calcium carbonate, generating a potentially useful end product from the captured carbon. But, as described above, precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater acidifies the seawater, reducing the ability of seawater to absorb CO2 from air. This proposed pathway is at a technology readiness level of ~5 and is currently undergoing small-scale field testing.

- Bazinet, Laurent; Geoffroy, Thibaud R. 2020. "Electrodialytic Processes: Market Overview, Membrane Phenomena, Recent Developments and Sustainable Strategies" Membranes 10, no. 9: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes10090221

- Lakshmanan, S. and Murugesan, T. (2014) ‘The chlor-alkali process: Work in Progress’, Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 16(2), pp. 225–234.

- Erika Callagon La Plante, Dante A. Simonetti, Jingbo Wang, Abdulaziz Al-Turki, Xin Chen, David Jassby, and Gaurav N. Sant ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (3), 1073-1089 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

- Mai, T. (2015) Technology Readiness Level, NASA. Brian Dunbar. Available at: http://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/scan/engineering/technology/txt_accordion1.html

CDR Potential

- Scalability - Given the immense stocks of dissolved inorganic carbon in seawater (~38,000 Gt (Ciais et al., 2013)), the theoretical scale of carbon capture from electrochemical methods is limitless for all practical intents and purposes. However, engineering, economic, political, and social considerations are likely to significantly reduce this upper bound. These include, but are not limited to:

-

- Access to low or zero-carbon emissions energy and infrastructure (e.g., desalination plants, offshore wind) with the ability to pump large quantities of seawater into large-scale electrochemical reaction cells, perform electrodialysis or electrolysis, and capture outputs and byproducts. The exact energy and infrastructure needs are pathway-dependent. For instance, electrolysis requires more energy than does electrodialysis, but the relative value of beneficial products (e.g., H2, O2 in electrolysis, HCl in electrodialysis) produced by each process must also be considered (Campione et al., 2018).

- In the cases where electrodialysis is used to produce HCl and strip CO2 gas out of seawater or used to produce NaOH that precipitates calcium carbonate, the cost is high (>$350/ton CO2) because of the cost of pumping seawater (Eisaman et al., 2018), and in the case of CO2 stripping, the additional cost of safely storing or utilizing the captured CO2 (Eisaman, 2020)

- Costs can be lowered to ~$100/ton CO2 if captured CO2 is stored in the ocean as bicarbonate due to the elimination of seawater pumping costs5

- Electrolytic pathways may offer CDR for $150-100/ton CO2, depending upon whether revenues generated from co-products are used to offset gross costs of CO2 capture (Callagon La Plante et al., 2021).

- The collective market size for a suite of co-products and services offered, including concentrated CO2, H2, O2, HCl, control over critical seawater chemistry parameters like pH and total alkalinity, and CDR.

- Access to low or zero-carbon emissions energy and infrastructure (e.g., desalination plants, offshore wind) with the ability to pump large quantities of seawater into large-scale electrochemical reaction cells, perform electrodialysis or electrolysis, and capture outputs and byproducts. The exact energy and infrastructure needs are pathway-dependent. For instance, electrolysis requires more energy than does electrodialysis, but the relative value of beneficial products (e.g., H2, O2 in electrolysis, HCl in electrodialysis) produced by each process must also be considered (Campione et al., 2018).

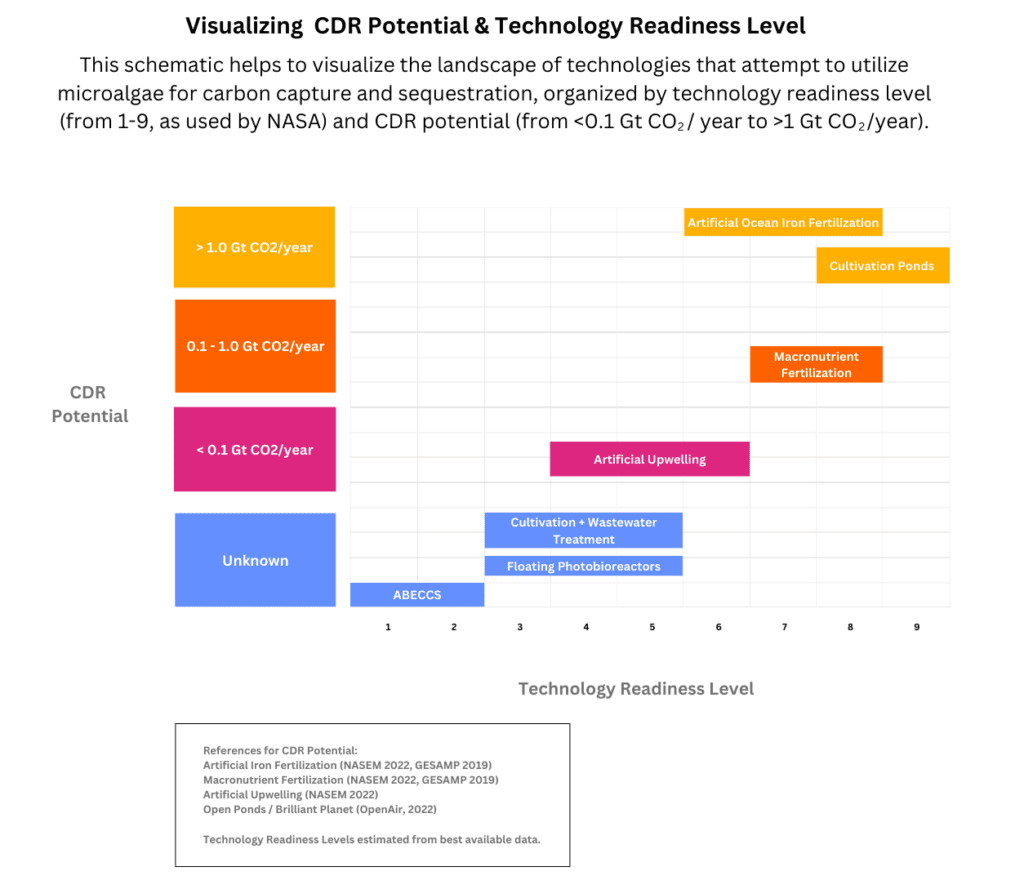

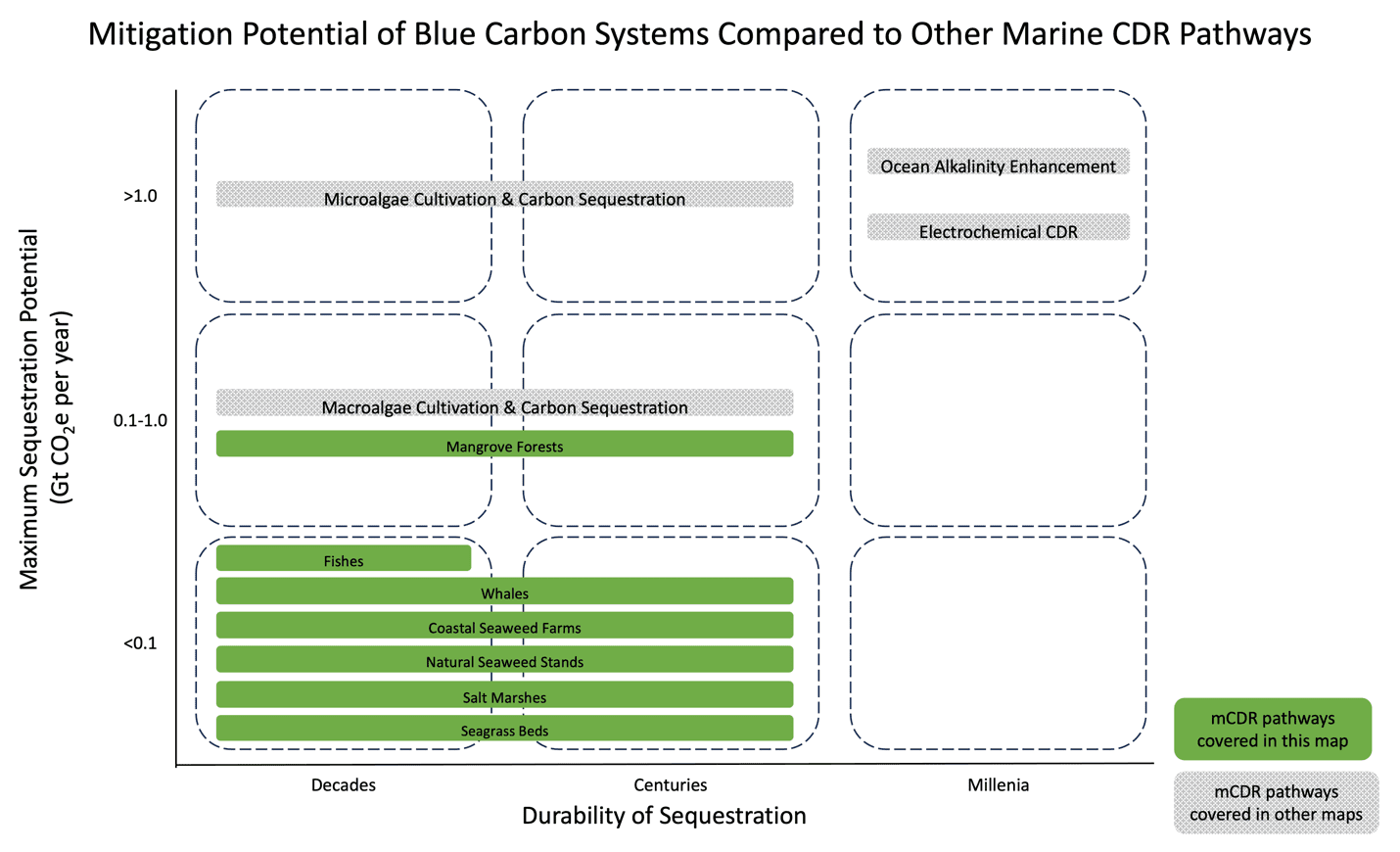

Ranges from recent synthesis reports vary with the 2021 NASEM report suggesting a range of 0.1-1.0 GtCO2/yr with medium confidence, while the 2023 synthesis report from NOAA suggests 1-10 GtCO2/yr.

- Sequestration Permanence - Electrochemical methods that produce reactive alkaline minerals (e.g., NaOH) will result in additional CO2 from the atmosphere being sequestered in the ocean as bicarbonate ions, which cannot exchange with the atmosphere. This is the same process that results in CO2 sequestration for rock-based forms of ocean alkalinity enhancement. The residence time of bicarbonate ions in the ocean is ~10,000 years, suggesting that electrochemical alkalinity production will generate CO2 sequestration with permanence of ~10,000 years.

Electrochemical methods that produce carbonate mineral products (e.g., Callagon La Plante et al., 2021) with sequestered carbon are stable on timescales of hundreds to thousands of years.

Electrochemical methods that capture and remove CO2 gas from seawater have variable permanence depending upon the storage location for the captured CO2. If the captured CO2 is sequestered in geologic storage, permanence can be long (thousands to millions of years)

- Ciais, P., C. Sabine, G. Bala, L. Bopp, V. Brovkin, J. Canadell, A. Chhabra, R. DeFries, J. Galloway, M. Heimann, C. Jones, C. Le Quéré, R.B. Myneni, S. Piao and P. Thornton, 2013: Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- Campione, A., L. Gurreri, M. Ciofalo, G. Micale, A. Tamburini, and A. Cipollina. “Electrodialysis for Water Desalination: A Critical Assessment of Recent Developments on Process Fundamentals, Models and Applications.” Desalination 434 (May 2018): 121–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.12.044.

- Eisaman, Matthew D., Jessy L.B. Rivest, Stephen D. Karnitz, Charles-François de Lannoy, Arun Jose, Richard W. DeVaul, and Kathy Hannun. “Indirect Ocean Capture of Atmospheric CO2: Part II. Understanding the Cost of Negative Emissions.” International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 70 (March 2018): 254–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2018.02.020.

- Eisaman, Matthew D. “Negative Emissions Technologies: The Tradeoffs of Air-Capture Economics.” Joule 4, no. 3 (March 2020): 516–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2020.02.007

- Rau, G.H. (2021) ‘Testimony to The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: A Research Strategy for Ocean Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration’ 27-January-2021.

- Erika Callagon La Plante, Dante A. Simonetti, Jingbo Wang, Abdulaziz Al-Turki, Xin Chen, David Jassby, and Gaurav N. Sant ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (3), 1073-1089 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2022. A Research Strategy for Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26278.

- Energy Futures Initiative. “Uncharted Waters: Expanding the Options for Carbon Dioxide Removal in Coastal and Ocean Environments.” December 2020.

- Erika Callagon La Plante, Dante A. Simonetti, Jingbo Wang, Abdulaziz Al-Turki, Xin Chen, David Jassby, and Gaurav N. Sant ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (3), 1073-1089 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

Environmental Co-benefits

- Electrochemical CDR would likely provide localized reductions in ocean acidification, with expected benefit(s) to marine ecosystems.

- Carbon-negative byproducts from electrochemical CDR can be substituted for more C-intensive sources (Rau, 2008):

- Electrolysis: hydrogen gas, chlorine gas, and oxygen gas, as well as hydrochloric acid

- Electrodialysis: hydrochloric acid

- In comparison to rock-based forms of alkalinity enhancement, electrochemical methods may offer:

- Reduced risk of toxicity from metals present in rock-based forms of alkalinity addition (Hartmann et al., 2013).

- However, the purity of outputs from electrochemical CDR is determined partially by the purity of the input materials to the electrochemical processes, and purer input materials are more expensive.

- Unlike ocean liming and coastal enhanced weathering, electrochemical alkalinity additions will not increase the silica concentration in the ocean and, therefore, may offer a reduced risk of disturbing phytoplankton community dynamics between calcifiers and silicifiers (Bach et al., 2019).

- Rau, Greg H. “Electrochemical Splitting of Calcium Carbonate to Increase Solution Alkalinity: Implications for Mitigation of Carbon Dioxide and Ocean Acidity.” Environmental Science & Technology 42, no. 23 (December 2008): 8935–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/es800366q.

- Hartmann, J., A. J. West, P. Renforth, P. Köhler, C. L. De La Rocha, D. A. Wolf-Gladrow, H. H. Dürr, and J. Scheffran (2013), Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification, Rev. Geophys., 51, 113–149, doi:10.1002/rog.20004.

- Bach LT, Gill SJ, Rickaby REM, Gore S and Renforth P (2019) CO2 Removal With Enhanced Weathering and Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement: Potential Risks and Co-benefits for Marine Pelagic Ecosystems. Front. Clim. 1:7. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2019.00007

Environmental Risks

- Risks Shared by Electrolysis and Electrodialysis

- The potential for changes in water column particle concentrations, turbidity, and optical properties if precipitation (inorganic mineral formation) of carbonates occurs due to local increases in alkalinity and pH.

- Mortality of marine life through seawater intake pumps and filters

- Shifts in phytoplankton, invertebrate and vertebrate physiology, competition and/or mortality due to decreases in acidity as CO2 is removed and/or alkalinity is added (Renforth & Henderson, 2017). For example, do the preceding seawater chemistry changes provide an increased competitive advantage for calcifiers over and above the restoration of calcifiers/calcification from ongoing ocean acidification?

- Risks about permanence and impacts of elevated concentrations of bicarbonate in the oceans.

- Risks Specific to Electrolysis

- Chlorine gas production and handling

- Risks Specific to Electrodialysis

- Production of large quantities of acid via electrodialysis that must be safely consumed or neutralized (e.g., via reaction with alkaline minerals).

- For pathways that strip CO2 gas from seawater and sequester the CO2, risks of permanence of storage and potential for leakage

- For pathways that remove dissolved inorganic carbon from seawater as calcium carbonate (Callagon La Plante et al., 2021), the impacts of large quantities of new calcium carbonate on the diversity, abundance, and ecosystem function of marine environments

- Renforth, P., and G. Henderson (2017), Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration, Rev. Geophys., 55, 636–674, doi:10.1002/2016RG000533.

- Erika Callagon La Plante, Dante A. Simonetti, Jingbo Wang, Abdulaziz Al-Turki, Xin Chen, David Jassby, and Gaurav N. Sant ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (3), 1073-1089 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

Social Co-benefits

- Localized reductions in ocean acidification, with expected benefit(s) to industries that rely on these localized improvements such as aquaculture and tourism

- Creation of employment in industries producing carbon-negative byproducts from electrochemical CDR (Rau, 2008):

- Electrolysis: hydrogen gas, chlorine gas, and oxygen gas, as well as hydrochloric acid

- Electrodialysis: hydrochloric acid

- OceanNETs Work Package 1: Economic Prospects and Incentives https://www.oceannets.eu/work-package-1-economic-prospects-and-incentives/

- Rau, Greg H. “Electrochemical Splitting of Calcium Carbonate to Increase Solution Alkalinity: Implications for Mitigation of Carbon Dioxide and Ocean Acidity.” Environmental Science & Technology 42, no. 23 (December 2008): 8935–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/es800366q.

Social Risks

- Renforth, P., and G. Henderson (2017), Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration, Rev. Geophys., 55, 636–674, doi:10.1002/2016RG000533.

- Erika Callagon La Plante, Dante A. Simonetti, Jingbo Wang, Abdulaziz Al-Turki, Xin Chen, David Jassby, and Gaurav N. Sant ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021 9 (3), 1073-1089 DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

Development Gaps and Needs

Development Gaps and Needs

Addressing Knowledge Gaps

- Electrochemical technologies, as applied to mCDR, are very new. Because most field experiments are in the planning phases or are underway currently, it is not yet possible to have a comprehensive characterization of benefits, risks, and scaling considerations of electrochemical approaches in real-world settings (i.e. not benchtop). Controlled field experiments across diverse ecosystems to determine marine chemistry and biology impacts and feedbacks are needed (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials).

- It is challenging to verify additional CO2 uptake from the atmosphere as a result of electrochemical CDR given the ocean’s dynamic CO2 flux “background state”. New methodologies are needed to observe additional sequestration from the atmosphere into the ocean (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Laboratory experiments are needed across a range of seawater chemistries because of expected electrochemical CDR variations in seawater total alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon1 to characterize environmental impacts (Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials).

- Look to the ocean acidification community’s effort to develop standardized protocols for guidance (Gattuso et al., 2015) as the community builds out standardized protocols and treatment levels for consistency and inter-comparability. See the 2023 Guide to Best Practices in Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement as one example (note that while not all electrochemistry is OAE, there is much in common and there are overlapping needs).

- Global, local, and regional predictions of physical, chemical, and biological outcomes and feedbacks of electrochemical CDR from high-resolution models (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation)

- Life cycle assessments to calculate net CDR benefits, taking into account all emissions associated with supply chains (Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols).

- Comments from Dr. Ros Rickaby, ‘Workshop on Ocean-based CDR Opportunities and Challenges, Part 2: Technological and Natural Approaches to Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement and CO2 Removal’ on 27th January 2021

- Gattuso, Jean-Pierre, and Lina Hansson. “European Project on Ocean Acidification (EPOCA): Objectives, Products, and Scientific Highlights.” Oceanography 22, no. 4 (December 1, 2009): 190–201. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2009.108.

Engineering Challenges and Needs

- Current observational technologies (sensors, ROVs, AUVs, etc.) and modeling tools are not widespread and easily available to support field trials with the necessary spatial and temporal frequency of monitoring and sampling (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- In the case of surface seawater alkalinity addition from electrolysis or electrodialysis, cost-effective and safe methods need to be developed that optimize the distribution, dispersal and dilution of any strong chemical bases to avoid impacts of excessively alkaline (pH>9) waters on marine ecosystems. Dilution may require pumping large amounts of seawater, which need to be optimized for energy and cost (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Offshore deployment of either electrodialysis or electrolysis would require further development to overcome challenges of working in the ocean (corrosion, biofouling, storms, physical and chemical stress on electrodes, catalysts, and membranes, etc.) (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Questions remain about how variations in seawater particulate and dissolved organic matter, temperature, and salinity affect electrochemical CDR efficiency (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

-

- Methods of handling chlorine gas produced as a byproduct of seawater electrolysis are needed (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations, Improve Understanding of Markets for Co-Products)

- Development of feedback control systems that integrate nearby observational data to determine optimal levels of electrochemical CDR (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Identifying and understanding how equipment, energy, and cost scale from benchtop experiments to small field experiments to globally-relevant deployments (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations, Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols, Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships)

-

Engineering Challenges and Needs

- Current observational technologies (sensors, ROVs, AUVs, etc.) and modeling tools are not widespread and easily available to support field trials with the necessary spatial and temporal frequency of monitoring and sampling (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- In the case of surface seawater alkalinity addition from electrolysis or electrodialysis, cost-effective and safe methods need to be developed that optimize the distribution, dispersal and dilution of any strong chemical bases to avoid impacts of excessively alkaline (pH>9) waters on marine ecosystems. Dilution may require pumping large amounts of seawater, which need to be optimized for energy and cost (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Offshore deployment of either electrodialysis or electrolysis would require further development to overcome challenges of working in the ocean (corrosion, biofouling, storms, physical and chemical stress on electrodes, catalysts, and membranes, etc.) (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Questions remain about how variations in seawater particulate and dissolved organic matter, temperature, and salinity affect electrochemical CDR efficiency (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

-

- Methods of handling chlorine gas produced as a byproduct of seawater electrolysis are needed (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations, Improve Understanding of Markets for Co-Products). As an example, chlorine can be used to extract lipids from microalgae 1 and the oil can then be used to produce high density polyethylene 2 hull structures for offshore electrochemical CDR operations. As such, this chlorine management path may lead to a largely self replicating HDPE-based marine CDR infrastructure at the basic materials level. Self replicating offshore infrastructure is highly valuable for DOC operations and the USN is currently 3D printing thick walled HDPE submarines 3 yet offshore electrochemical and biomass CDR reactor hulls can simply be capped off extruded pipes of large diameter and lenght 4, no complex 3D production expense needed.

- Development of feedback control systems that integrate nearby observational data to determine optimal levels of electrochemical CDR (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- Identifying and understanding how equipment, energy, and cost scale from benchtop experiments to small field experiments to globally-relevant deployments (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations, Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols, Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships)

-

- Garoma, T., Yazdi, R.E. Investigation of the disruption of algal biomass with chlorine. BMC Plant Biol 19, 18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1614-9

- https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/12/8/1641/pdf

- https://3dprint.com/181795/navy-ornl-3d-printed-sub-hull/

- https://www.agru.at/en/applications/agruline/grand-opening-ready-for-the-next-level/

Public Awareness and Support Are Low

Many of the opportunities and challenges around building public support are not specific to electrochemical CDR, but there are several points of interest specific to electrochemical CDR:

- Electrochemical CDR faces challenges in terms of public perception regarding potential environmental risks not necessarily faced by more “nature-based” approaches, such as coastal blue carbon restoration (Bertram & Merk, 2020). (Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships)

- Complexities of electrochemical CDR pathways inhibit understanding and evaluation by non-technical audiences

- There is a great deal of uncertainty and confusion around any mCDR pathway that relies on adding materials to the ocean. This point applies to both electrochemical alkalinity additions, which return a base to the seawater, and pathways that precipitate out calcium carbonate.

- Earlier ocean iron fertilization experiments2 could offer opportunities to adopt best practices and avoid mistakes made when building public support for electrochemical CDR.

- Electrochemical CDR has the advantage that it can be “turned off” more easily than the other approaches, enabling great control over its application

- Clearer communication strategies need to be developed to respond to the “engineering” narrative of electrochemical CDR.

- Bertram C and Merk C (2020) Public Perceptions of Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal: The Nature-Engineering Divide? Front. Clim. 2:594194. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2020.594194

- Schiermeier, Q. (2009a). Ocean Fertilization Experiment Draws Fire: Indo-German Research Cruise Sets Sail Despite Criticism. Available online at: https://www. nature.com/news/2009/090109/full/news.2009.13.html

First-Order Priorities

First-Order Priorities

Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation

High-resolution data-assimilative models that can support real-world testing of electrochemical CDR are required. These modeling tools must:

- Account for complex interactions in the immediate vicinity of the electrochemical CDR and downstream impacts

- Provide four-dimensional (space and time) estimates of biogeochemistry in zone of influence both in the presence and absence of OAE. The difference between these two simulations can be used to inform CDR estimates that account for background variability in the ocean.

- CDR estimates from electrochemical CDR must include estimates of the “opportunity cost” of electrochemical CDR - how did electrochemical CDR shift phytoplankton community composition, production, and export?

To support the design of proof-of-concept field trials, these models should also:

- Provide estimates of the size and scale of biogeochemical modification to the ecosystem from electrochemical CDR, allowing for informed placement of sensors to monitor the field trials

- Be capable of simulating passive tracers (e.g. SF6) to inform whether and how these passive tracers may be useful in field trials (e.g., estimating rates of atmospheric CO2 uptake)

- Inform a prioritized set of predictions to be tested during field trials

Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials

Field trials for the various electrochemical CDR technologies are urgently needed to test both carbon sequestration potential and environmental impacts (both positive and negative). See the mCDR Field Trial Database for information on current field experiments. A series of steps are needed to get to a series of controlled field trials. They include:

Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials

Field trials for the various electrochemical CDR technologies are urgently needed to test both carbon sequestration potential and environmental impacts (both positive and negative). A series of steps are needed to get to a series of controlled field trials. They include:

Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations

A new suite of durable, seagoing technologies are needed to support electrochemical CDR RD&D. Technology development needs include:

- MEPC (1975) Method for calculation of dilution capacity in the ships wake. Submitted jointly by the Netherlands and Norway

Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols

Standardized methodologies from third parties to verify uptake of atmospheric CO2 resulting from electrochemical CDR will ultimately need to be developed to enable trading of carbon removal credits. Key first steps to support development of these protocols include:

- Convening experts to review advances from modeling tools (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation) and controlled field trials (Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials) to identify satisfied and outstanding data needs necessary to quantify additional CO2 uptake as a direct result of electrochemical CDR. As advances in electrochemical CDR RD&D are made, the satisfied and outstanding data needs will need to be updated.

- Apply existing (Koornneed & Nieuwlaar, 2009; Hartmann et al., 2013), or develop when necessary, life cycle analysis tools to calculate stored carbon after accounting for emissions from required materials, energy, transportation/dispersal, etc.

- Include aspects of sustained monitoring to verify CDR permanence over long time scales as CDR is scaled.

- Koornneed, J. and Nieuwlaar, E., 2009. Environmental life cycle assessment of CO2 sequestration through enhanced weathering of olivine. Working paper, Group Science, Technology and Society, Utrecht University.

- Hartmann, J., West, A.J., Renforth, P., Köhler, P., De La Rocha, C.L., Wolf‐Gladrow, D.A., Dürr, H.H. and Scheffran, J., 2013. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Reviews of Geophysics, 51(2), pp.113-149.

Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships

Research, development, and demonstration of electrochemical CDR may be accelerated and strengthened by creating partnerships with key industries/sectors, including:

- Offshore renewable energy production, including wind and others, both as power sources and as integrated CDR platforms

- Coastal industries, including desalination and wastewater treatment facilities, which already have infrastructure for pumping/processing seawater or wastewater for CO2 extraction or alkalinity addition.

- Marine research laboratories that already pump seawater and have expertise, technical equipment and infrastructure to support research and development

- Decommissioned or active offshore oil platforms, wells, and reservoirs as sites for CDR and CO2 sequestration.

- Finfish and shellfish aquaculture where the CDR-produced CO2 and/or alkalinity can be used to optimize chemical conditions, including providing relief from ocean acidification.

Developing and strengthening relationships with partner industries may also help promote public acceptance, as well as potentially offer faster routes to obtaining the necessary permitting.

Improve Understanding of Markets for Co-Products

Electrochemical CDR may generate a host of co-products. Assessing and mapping potential new markets to accommodate these co-products is an important step towards determining the feasibility of electrochemical CDR approaches at scale.

Potential co-products include:

- Hydrogen (H2) gas – as a fuel, energy storage medium, and as a feedstock

- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) – potentially to refine waste products from silicate mining (House et al., 2007)

- Oxygen (O2) gas

- Chlorine (Cl2) gas – can be combusted with H2 gas to form HCl

- House, Kurt Zenz, Christopher H. House, Daniel P. Schrag, and Michael J. Aziz. “Electrochemical Acceleration of Chemical Weathering as an Energetically Feasible Approach to Mitigating Anthropogenic Climate Change.” Environmental Science & Technology 41, no. 24 (December 2007): 8464–70. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0701816.

Macroalgae Cultivation and Carbon Sequestration

State of Technology

State of Technology

Overview

- FAO. 2018. The global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization. Globefish Research Programme Volume 124. Rome. 120 pp. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.fao.org/in-action/globefish/publications/details-publication/en/c/1154074/

- Thierry Chopin & Albert G. J. Tacon (2020): Importance of Seaweeds and Extractive Species in Global Aquaculture Production, Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, DOI: 10.1080/23308249.2020.1810626 https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Importance-of-Seaweeds-and-Extractive-Species-in-Chopin-Tacon/c6fd9ce938e29652280332fa65267c4af6f17066

- García-Poza, Sara, Adriana Leandro, Carla Cotas, João Cotas, João C. Marques, Leonel Pereira, and Ana M. M. Gonçalves. “The Evolution Road of Seaweed Aquaculture: Cultivation Technologies and the Industry 4.0.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18 (September 8, 2020): 6528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186528.

- Duarte CM, Wu J, Xiao X, Bruhn A and Krause-Jensen D (2017) Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation? Front. Mar. Sci. 4:100. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00100 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2017.00100/full

- "Running Tide". https://www.runningtide.com/removing

- GESAMP (2019). “High level review of a wide range of proposed marine geoengineering techniques”. (Boyd, P.W. and Vivian, C.M.G., eds.). (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UN Environment/ UNDP/ISA Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection). Rep. Stud. GESAMP No. 98, 144 p. http://www.gesamp.org/publications/high-level-review-of-a-wide-range-of-proposed-marine-geoengineering-techniques

- Krause-Jensen, D., Duarte, C. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nature Geosci 9, 737–742 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2790

- Hughes, Adam D., et al. “Does Seaweed Offer a Solution for Bioenergy with Biological Carbon Capture and Storage?” Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology, vol. 2, no. 6, 2012, pp. 402–407., doi:10.1002/ghg.1319.

- Moreira, D., Pires, J.C.M., 2016. Atmospheric CO2 capture by algae: Negative carbon dioxide emission path. Bioresource Technology 215, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.060

- Zhang, C., Zhang, L., Gao, J., Zhang, S., Liu, Q., Duan, P., Hu, X., 2020. Evolution of the functional groups/structures of biochar and heteroatoms during the pyrolysis of seaweed. Algal Research 48, 101900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2020.101900

- Roberts, D., Paul, N., Dworjanyn, S. et al. Biochar from commercially cultivated seaweed for soil amelioration. Sci Rep 5, 9665 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09665

- Chia, Wen Yi, et al. “Nature’s Fight against Plastic Pollution: Algae for Plastic Biodegradation and Bioplastics Production.” Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, vol. 4, 2020, p. 100065., doi:10.1016/j.ese.2020.100065.

- Siegel, D. A., DeVries, T., Doney, S. C., & Bell, T. (2021). Assessing the sequestration time scales of some ocean-based carbon dioxide reduction strategies. Environmental Research Letters, 16(10), 104003. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac0be0

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2022. A Research Strategy for Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26278

CDR Potential

- Carbon Capture - The ultimate CDR potential of large-scale macroalgal cultivation and sequestration is as yet difficult to determine. Recent consensus reports cite the following as possible carbon dioxide removal potential from macroalgae cultivation and sequestration:

- 0.1 – 1.0 Gt CO2/year (NASEM 2022)

- 0.1 – 0.6 Gt CO2/ year (NOAA 2023)

Theoretically, macroalgal cultivation and sequestration could be scaled to between 0.1 - 1.0 Gt CO2/year (NASEM 2022, NOAA 2023), but realized CDR may be much lower due to a number of factors, including:

-

- Competition for space with existing ocean stakeholders – commercial shipping, commercial fishing, indigenous rights, marine protected areas, non-seaweed aquaculture, etc.

- Challenges with expanding to offshore environments – engineering of moorings and farm structures, challenges with operations and maintenance in distant environments (Bak et al., 2020; Lovatelli et al., 2010), and the likely associated cost increases (at least at first) associated with offshore operations

- Most open ocean environments require nutrient additions to sustain macroalgal yields. If these nutrients come from the deep ocean, they will be accompanied by high CO2 water that can be released and will offset macroalgal carbon sequestration to some degree (which needs to be quantified) (Pan et al., 2016; Oschlies et al., 2009).

- If macroalgal farms are located closer to the coastal zone, excess anthropogenic nitrogen inputs could support ~3.5 million km2 of macroalgal cultivation, corresponding with an estimated CDR range of 5- 10 Gt CDR annually (NASEM workshop comments from Carlos Duarte, 2021), alleviating competition for “natural” nutrient supplies with phytoplankton and alleviating the need for an upwelled supply of nutrients (and the associated risks of releasing CO2 from upwelled deep ocean waters).

- It is hypothesized that macroalgae-based pathways could supply CDR at moderate cost ($25-125 per ton of CO2 removed) (Energy Futures Initiative, 2020; Capron et al., 2020; NASEM, 2022), but these cost estimates are preliminary and subject to change as macroalgae-based pathways advance in technological readiness.

- Researchers at UC Irvine have developed a biophysical-economic model (G-MACMODS) to better understand the geophysical, biological, and economic sensitivities of macroalgae-based CDR pathways (DeAngelo et al., 2022). Also, see the affiliated site suitability tool.

2. Sequestration Permanence -For cultivated macroalgae to contribute to CDR, the carbon captured in the macroalgal tissue needs to be sequestered to prevent its decomposition and return to the atmosphere. Sequestration pathways include:

-

- Intentionally sinking the macroalgae (pre- or post-processing) into the deep ocean (>1000 meters depth) where it can be sequestered from contact with the atmosphere for hundreds to a few thousand years (if remineralized in the deep ocean) or for thousands-to-millions of years (if buried in marine sediments) (GESAMP 2019).

- There are natural analogs to this process already. In macroalgal systems, already ~50% of natural macroalgal production breaks off and becomes dissolved or particulate organic matter. Some of the particulate organic matter is transported to the deep ocean, where the carbon is sequestered (Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016).

- Relying on sedimentary burial below or adjacent to the farm (typically more applicable for farms not located over deep water) (Duarte et al., 2023)

- Harvesting the macroalgae for:

- Bioenergy (Hughes et al., 2013)

- Combining combustion pathways with carbon capture and storage (thousands-to-millions of years if stored in a geologic reservoir) (Mereira & Pires, 2016)

- Pyrolysis, resulting in biochar (hundreds to thousands of years) (Zhang et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2015)

- Production of long-lived bioproducts, such as bioplastics, that are capable of permanent (>100 years) sequestration (Albright & Fujita, 2023; Chia et al., 2020)

- Bioenergy (Hughes et al., 2013)

- Intentionally sinking the macroalgae (pre- or post-processing) into the deep ocean (>1000 meters depth) where it can be sequestered from contact with the atmosphere for hundreds to a few thousand years (if remineralized in the deep ocean) or for thousands-to-millions of years (if buried in marine sediments) (GESAMP 2019).

3. Differentiating from Avoided Emissions - Macroalgae can provide a number of other services that either reduce or replace greenhouse gas emissions, but do not remove legacy carbon dioxide pollution from the atmosphere. One example of reducing emissions: red algal supplements added to cattle feed may play a key role in reducing enteric methane emissions from cattle by over 50% (Roque et al., 2019; Vijn et al., 2020). Given methane’s potency as a greenhouse gas, such emissions reductions may play an outsized role in slowing planetary temperature increases through the reduction of greenhouse gases. Macroalgae biomass may also be converted into short-lived, high-value bioproducts, such as food and nutritional supplements (Biris-Dorhoi et al., 2020). This process may contribute to avoided emissions if it substitutes for carbon-intensive feedstocks, but it does not represent CDR because of the short timescale over which these products sequester carbon before it returns to the atmosphere. Although the focus of this roadmap is on macroalgae pathways for CDR, many of the obstacles faced, development needs, and near-term opportunities for advancement are relevant to these associated pathways for avoided greenhouse gas emissions.

- Energy Futures Initiative. “Uncharted Waters: Expanding the Options for Carbon Dioxide Removal in Coastal and Ocean Environments.” December 2020. https://efifoundation.org/reports/uncharted-waters/

- Bak, Urd Grandorf, Gregersen, Ólavur and Infante, Javier. "Technical challenges for offshore cultivation of kelp species: lessons learned and future directions" Botanica Marina, vol. 63, no. 4, 2020, pp. 341- 353. https://doi-org.oca.ucsc.edu/10.1515/bot-2019-0005 https://www.sciencegate.app/document/10.1515/bot-2019-0005

- Lovatelli, A., Aguilar-Manjarrez, J. and Soto, D. (2013). Expanding mariculture farther offshore: technical, environmental, spatial and governance challenges. In: FAO Technical Workshop, 22–25 March 2010, Orbetello, Italy. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Proceedings No. 24. FAO, Rome, p. 73. https://www.fao.org/3/i3092e/i3092e00.htm

- Pan, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, D. et al. Research progress in artificial upwelling and its potential environmental effects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 236–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-015-5195-2

- Oschlies, A., Pahlow, M., Yool, A., and Matear, R. J. (2010), Climate engineering by artificial ocean upwelling: Channelling the sorcerer's apprentice, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L04701, doi:10.1029/2009GL041961.

- Comments from C. Duarte, ‘A Workshop on Ocean-based CDR Opportunities and Challenges Part 3: Ecosystem Recovery & Seaweed Cultivation’. A Research Strategy for Ocean Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration: Workshop Series, Part 3. 2nd February 2021. Accessible at: https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/02-02-2021/a-research-strategy-for-ocean-carbon-dioxide-removal-and-sequestration-workshop-series-part-3

- EFI Report. “Uncharted Waters: Expanding the Options for Carbon Dioxide Removal in Coastal and Ocean Environments.” December 2020.

- Capron ME, Stewart JR, de Ramon N’Yeurt A, Chambers MD, Kim JK, Yarish C, Jones AT, Blaylock RB, James SC, Fuhrman R, Sherman MT, Piper D, Harris G, Hasan MA. Restoring Pre-Industrial CO2 Levels While Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Energies. 2020; 13(18):4972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184972

- TRL definitions: https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/scan/engineering/technology/txt_accordion1.htm

- Sustainable Seaweed Solutions, https://www.ess.uci.edu/~sjdavis/seaweed.html

- GESAMP (2019). “High level review of a wide range of proposed marine geoengineering techniques”. (Boyd, P.W. and Vivian, C.M.G., eds.). (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UN Environment/ UNDP/ISA Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection). Rep. Stud. GESAMP No. 98, 144 p. http://www.gesamp.org/publications/high-level-review-of-a-wide-range-of-proposed-marine-geoengineering-techniques

- Krause-Jensen, D., Duarte, C. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nature Geosci 9, 737–742 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2790

- Hughes, Adam D., et al. “Does Seaweed Offer a Solution for Bioenergy with Biological Carbon Capture and Storage?” Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology, vol. 2, no. 6, 2012, pp. 402–407., doi:10.1002/ghg.1319.

- Moreira, D., Pires, J.C.M., 2016. Atmospheric CO2 capture by algae: Negative carbon dioxide emission path. Bioresource Technology 215, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.060

- Zhang, C., Zhang, L., Gao, J., Zhang, S., Liu, Q., Duan, P., Hu, X., 2020. Evolution of the functional groups/structures of biochar and heteroatoms during the pyrolysis of seaweed. Algal Research 48, 101900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2020.101900

- Roberts, D., Paul, N., Dworjanyn, S. et al. Biochar from commercially cultivated seaweed for soil amelioration. Sci Rep 5, 9665 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09665

- Chia, Wen Yi, et al. “Nature’s Fight against Plastic Pollution: Algae for Plastic Biodegradation and Bioplastics Production.” Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, vol. 4, 2020, p. 100065., doi:10.1016/j.ese.2020.100065.

- Roque, B.M., Salwen, J.K., Kinley, R., Kebreab, E., 2019. Inclusion of Asparagopsis armata in lactating dairy cows’ diet reduces enteric methane emission by over 50 percent. Journal of Cleaner Production 234, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.193

- Vijn S. et al.,2020. Key Considerations for the Use of Seaweed to Reduce Enteric Methane Emissions From Cattle. Front. Vet. Sci., 23 December 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.597430 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.597430/full

- Biris-Dorhoi ES, Michiu D, Pop CR, Rotar AM, Tofana M, Pop OL, Socaci SA, Farcas AC. Macroalgae A Sustainable Source of Chemical Compounds with Biological Activities. Nutrients. 2020 Oct 11;12(10):3085. doi: 10.3390/nu12103085. PMID: 33050561; PMCID: PMC7601163.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2022. A Research Strategy for Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26278. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/a-research-strategy-for-ocean-carbon-dioxide-removal-and-sequestration

Environmental Co-benefits

- Localized buffering/reductions in ocean acidification due to CO2 uptake. (Koweek et al., 2016; Hirsh et al., 2020; Kapsenberg & Cyronak 2019; Fernández et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2021)

- Nutrient remediation and metal uptake in eutrophied, polluted coastal waters (Neveux et al., 2018)

- Building macroalgae cultivation facilities near shellfish or fish aquaculture facilities may alleviate negative impacts from such activities (NASEM 2022) (e.g., deoxygenation, eutrophication)

- Macroalgae farms may attenuate wave energy (Mork, 1996)

- Creation of habitat with resulting nurseries for fish and other marine life (Smale et al., 2013)

- Carbon capture at sea may reduce the demand for terrestrial-based CDR alternatives that compete for land and/or freshwater

- Koweek, D. A., Nickols, K. J., Leary, P. R., Litvin, S. Y., Bell, T. W., Luthin, T., Lummis, S., Mucciarone, D. A., and Dunbar, R. B.: A year in the life of a central California kelp forest: physical and biological insights into biogeochemical variability, Biogeosciences, 14, 31–44, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-31- 2017, 2017.

- Hirsh, H. K., Nickols, K. J., Takeshita, Y., Traiger, S. B., Mucciarone, D. A., Monismith, S., et al. (2020). Drivers of biogeochemical variability in a central California kelp forest: Implications for local amelioration of ocean acidification. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125, e2020JC016320. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JC016320

- Kapsenberg, L, Cyronak, T. Ocean acidification refugia in variable environments. Glob Change Biol. 2019; 25: 3201– 3214. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14730

- Pamela A. Fernández, Pablo P. Leal & Luis A. Henríquez (2019) Co-culture in marine farms: macroalgae can act as chemical refuge for shell-forming molluscs under an ocean acidification scenario, Phycologia, 58:5, 542-551, DOI: 10.1080/00318884.2019.1628576

- Xiao, X., Agustí, S., Yu, Y., Huang, Y., Chen, W., Hu, J., Li, C., Li, K., Wei, F., Lu, Y. and Xu, C., 2021. Seaweed farms provide refugia from ocean acidification. Science of The Total Environment, 776, p.145192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145192

- Neveux, N., Bolton, J., Bruhn, A., Roberts, D., Ras, M., 2017. The Bioremediation Potential of Seaweeds: Recycling Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Other Waste Products. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527801718.ch7

- Mork, M. (1996). “Wave attenuation due to bottom vegetation,” in Waves and Nonlinear Processes in Hydrodynamics, eds J. Grue, B. Gjevik, and J. E. Weber (Oslo: Kluwer Academic Publishing), 371–382.

- Smale, D.A., Burrows, M.T., Moore, P., O’Connor, N., Hawkins, S.J., 2013. Threats and knowledge gaps for ecosystem services provided by kelp forests: a northeast Atlantic perspective. Ecology and Evolution 3, 4016–4038. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.774

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2022. A Research Strategy for Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26278.

Environmental Risks

- Macroalgae are known to release bromoform and other halomethanes (Carpenter et al., 2009; Mehlmann et al., 2020) , and thus, large-scale macroalgae cultivation seems likely to increase the release of these substances. This needs additional research as the natural marine sources of these gases are currently estimated to be responsible for around 9% of stratospheric ozone loss, including depletion due to anthropogenic causes (Tegtmeier et al., 2015).

- Production of methane, nitrous oxide, and other potentially hazardous gases by the macroalgae

- The potential for CO2 outgassing from pumping deep water to the surface (artificial upwelling) to supply needed nutrients for the macroalgae (Pan et al., 2015).

- Ecological and biogeochemical (especially acidification and hypoxia) impacts in the deep sea from sinking large quantities of macroalgae into the deep ocean

- Such effects are likely to be location-specific

- The remineralization of sunken seaweed may lead to oxygen depletion and acidification (Wu et al., 2023, Ocean Visions 2022)

- Impacts to biodiversity and ecosystem function from large-scale cultivation operations, including (Campbell et al., 2019):

- Enhanced disease and parasite risk

- Alteration of population genetics

- Introduction of non-native species into new environments

- Enhancement in epiphytic calcifiers that could offset carbon sequestration through calcification-induced CO2 release

- Reduced phytoplankton production in and around large macroalgae farms due to competition for nutrients and light

- Ecological and biogeochemical (especially acidification and hypoxia) impacts in the deep sea from sinking large quantities of macroalgae into the deep ocean

- Such effects are likely to be location-specific

- Changes in light and nutrient availability (including possible changes in ocean albedo)

- In near-coastal zones, changes in circulation patterns due to drag by the seaweed could change residence time in nearshore environments

- Changes in coastal residence time may affect the prevalence and intensity of harmful algal blooms (HABs)

- Entanglement of marine megafauna (e.g., whales)

- Campbell, Iona, et al. “The Environmental Risks Associated With the Development of Seaweed Farming in Europe - Prioritizing Key Knowledge Gaps.” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 6, 2019, doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00107.

- Campbell I, Macleod A, Sahlmann C, Neves L, Funderud J, Øverland M, Hughes AD and Stanley M (2019) The Environmental Risks Associated With the Development of Seaweed Farming in Europe - Prioritizing Key Knowledge Gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:107. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00107

- Pan, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, D. et al. Research progress in artificial upwelling and its potential environmental effects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 236–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-015-5195-2

- Carpenter, L. J., et al. “Air-Sea Fluxes of Biogenic Bromine from the Tropical and North Atlantic Ocean.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, vol. 9, no. 5, 2009, pp. 1805–1816., https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1805-2009.

- Mehlmann, Melina, et al. “Natural and Anthropogenic Sources of Bromoform and Dibromomethane in the Oceanographic and Biogeochemical Regime of the Subtropical North East Atlantic.” Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, vol. 22, no. 3, 2020, pp. 679–707., https://doi.org/10.1039/c9em00599d.

- Tegtmeier, S., Ziska, F., Pisso, I., Quack, B., Velders, G. J. M., Yang, X., and Krüger, K.: Oceanic bromoform emissions weighted by their ozone depletion potential, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 13647–13663, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-13647-2015, 2015.

Social Co-benefits

- Job Creation: Seaweed farming could also present new job opportunities for fishers whose work is threatened by climate change (e.g., seaweed farming at Atlantic Sea Farms).

- Value-Added Products: High-value bioproducts (pigments, lipids, proteins, etc) can replace more carbon-intensive alternatives in feed, food, fuel, and other commodities (Albright & Fujita, 2023).

- Duarte CM, Wu J, Xiao X, Bruhn A and Krause-Jensen D (2017) Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation? Front. Mar. Sci. 4:100. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00100

- Campbell I, Macleod A, Sahlmann C, Neves L, Funderud J, Øverland M, Hughes AD and Stanley M (2019) The Environmental Risks Associated With the Development of Seaweed Farming in Europe - Prioritizing Key Knowledge Gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:107. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00107

- Pan, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, D. et al. Research progress in artificial upwelling and its potential environmental effects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 236–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-015-5195-2

- https://atlanticseafarms.com/pages/meet-our-farmers

Social Risks

- Competition for Space: Competition for space with existing ocean stakeholders – commercial shipping, commercial fishing, indigenous rights, marine protected areas, non-seaweed aquaculture, etc.

- Potential for entanglement of macroalgae cultivation equipment with shipping, commercial fishing gear, aquaculture farms etc, particularly if the macroalgae farm is free floating

- Protected sites include marine protected areas, world heritage sites, culturally significant areas, treaty-protected resources, ecologically or biologically significant marine areas, sensitive or vulnerable marine ecosystems, marine protected areas, and other effective area-based conservation measures.

- Competition for Food: Given that macroalgae can be converted to nutrient dense food stuffs, there may also be social resistance to this method as it involves the willful destruction of viable food sources that could be used in furtherance of human food security (Stedt et al., 2022)

- Financing: Financing any CDR approach brings with it the risk of creating inequity and decreasing social welfare (Cooley et al., 2022). With macroalgae cultivation, this may be especially applicable to coastal dwelling communities who rely on the ocean for their livelihoods, food, and cultural meaning.

- Campbell, Iona, et al. “The Environmental Risks Associated With the Development of Seaweed Farming in Europe - Prioritizing Key Knowledge Gaps.” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 6, 2019, doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00107.

- Campbell I, Macleod A, Sahlmann C, Neves L, Funderud J, Øverland M, Hughes AD and Stanley M (2019) The Environmental Risks Associated With the Development of Seaweed Farming in Europe - Prioritizing Key Knowledge Gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:107. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00107

- Pan, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, D. et al. Research progress in artificial upwelling and its potential environmental effects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 236–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-015-5195-2

- Cooley, Sarah R., et al. “Sociotechnical Considerations about Ocean Carbon Dioxide Removal.” Annual Review of Marine Science, vol. 15, no. 1, 2023, pp. 41–66., https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032122-113850.

Development Gaps and Needs

Development Gaps and Needs

Addressing Knowledge Gaps

- Proof-of-concept field experiments have not been conducted in open ocean conditions to test growth rates, sequestration potential, and environmental impacts of macroalgal CDR pathways (Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials)

- Siting analyses are needed to identify optimal nutrient, light, and wave conditions for growth; as well as potential conflicts with other marine industries (such as the NOAA Coastal Aquaculture Siting and Sustainability toolkit) (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation)

- A suite of tools and methodologies to estimate productivity, carbon capture, export, and sequestration, including direct and remote sensing approaches1 needs to be built (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Measure the Scale and Impacts of CDR via Macroalgae Sinking, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations).

- For sinking pathways, the challenges of following the carbon from source (farm) to deposition (seafloor) in energetically active environments (horizontal and vertical currents, turbulent areas, etc.)

- We do not understand enough about the net CDR benefit from a life cycle perspective (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations, Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols)

- Challenges exist verifying additional CO2 uptake from the atmosphere to the ocean in a dynamic background as a result of macroalgae cultivation and sequestration CDR pathways (Hurd et al., 2023; Burger et al., 2023)(Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Inclusion of various macroalgal CDR into integrated assessment models to simulate and predict complex, global responses to macroalgal CDR. Examples include changes in CO2 fluxes in other ecosystems via teleconnections (connections in Earth processes and non-continuous geographic regions, which are often caused by processes not immediately apparent from first principles), and to estimate permanence via the various macroalgal CDR pathways (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation)

- Increased knowledge base regarding the physiology (including heat tolerance) and genomics of a broader array of potential cultivars – beyond the ten most common - to understand their growth and carbon sequestration potential is needed (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials)

- Better understanding of how large-scale macroalgae cultivation affects the partitioning of carbon between particulate and dissolved phases, and its implications for CDR (Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation, Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials)

- Bell TW, Nidzieko NJ, Siegel DA, Miller RJ, Cavanaugh KC, Nelson NB, Reed DC, Fedorov D, Moran C, Snyder JN, Cavanaugh KC, Yorke CE and Griffith M (2020) The Utility of Satellites and Autonomous Remote Sensing Platforms for Monitoring Offshore Aquaculture Farms: A Case Study for Canopy Forming Kelps. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:520223. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.520223

Engineering Challenges and Needs

- Advances are needed in offshore mooring design, as well as viable, durable, and cost-effective farming systems for offshore cultivation technology (Bak et al., 2020). (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Current observational technologies (sensors, ROVs, AUVs, etc.) and modeling tools are not widespread or easily available to support field trials with the necessary spatial and temporal frequency of monitoring and sampling (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Technologies to accelerate macroalgal sinking are not well explored or understood (Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials, Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Wave-powered devices (both for electrical power and upwelling) are in their infancy (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Upwelling systems must be designed and tested to access deeper water nutrients and keep them in the euphotic zone where they can support macroalgal growth (as opposed to immediately sinking out of the euphotic zone)

- Harvesting and processing technologies that minimize environmental impact and energy use are needed (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- More efficient means of drying the harvested crop (for non-sinking pathways)

- Technologies to scale shore-based hatcheries to produce more juvenile kelp ready for outplanting are needed (Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations)

- Bak, Urd Grandorf, Gregersen, Ólavur and Infante, Javier. "Technical challenges for offshore cultivation of kelp species: lessons learned and future directions" Botanica Marina, vol. 63, no. 4, 2020, pp. 341-353. https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2019-0005

Building a Global Workforce

- Training, skills development, and technology transfers are needed globally to expand available workforce for macroalgal cultivation and sequestration (Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships, Broaden Funding Base for RD&D, Growing & Maintaining Public Support)

- Stable, increased research and development funding to build capacity in this sector, such as has been seen with the ARPA-E MARINER program in the US (Broaden Funding Base for RD&D)

Building a Seaweed Carbon Market

- Certification standards for macroalgal carbon sequestration are needed to support developing markets for macroalgae CO2 sequestration (Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols)

- Scalable business models and markets to support demand for the multitude of potential products that can be derived from macroalgae (nutritional supplements, high value food items, additives, biochar, bioenergy, etc.) are needed to support this industry (Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships, Broaden Funding Base for RD&D, Growing & Maintaining Public Support)

- A standard for mCDR is still needed. Evidence of a move towards a standard for seaweed can be seen in Verra's Seascape Carbon Initiative.

Public Awareness and Support Are Low

While interests and awareness amongst researchers and technologists is growing (i.e., Pessarrodona et al., 2023; DeAngelo et al., 2022; Troell et al., 2024), public awareness and support remain low. Many of the obstacles and needs around building and maintaining public support are not specific to macroalgal cultivation and sequestration, but there are a few points of interest specific to macroalgal cultivation pathways (Growing & Maintaining Public Support):

- Industrial-scale farms could have a negative public connotation (e.g. corn fields/monoculture in the ocean)

- If genetically modified macroalgae were to be used to increase cultivation yields and sequestration potential, especially in the context of industrial-scale macroalgae farms, that might be perceived negatively by the public given public views on genetically modified organisms

- Public perceptions of sinking macroalgal may differ from perceptions about conversion of cultivated macroalgae into high value bio products

First-Order Priorities

First-Order Priorities

Develop New Modeling Tools to Support Design and Evaluation

High-resolution data-assimilative models are needed to support real-world testing of macroalgal CDR pathways. These modeling tools must:

- Account for complex interactions in the vicinity of the farm and downstream impacts (van der Molen et al., 2018; Coastal Dynamics Laboratory)

- Provide four-dimensional (space and time) estimates of biogeochemistry in zone of influence both in the presence and absence of macroalgae cultivation. The difference between these two simulations can be used to inform CDR estimates that account for background variability in the ocean.

- CDR estimates from macroalgae must include estimates of the “opportunity cost” of macroalgal carbon sequestration (how much production and export would have occurred in natural phytoplankton communities in the absence of a macroalgal farm?) as well as any enhancements to marine ecosystem productivity due to the presence of a macroalgal farm (is phytoplankton production enhanced above background levels due to the presence of macroalgae farms?).

To support the design of proof-of-concept field trials, these models should also:

- Provide estimates of the size and scale of biogeochemical modification to the ecosystem from macroalgae cultivation, allowing for informed placement of sensors to monitor the field trials.

- Be capable of simulating passive tracers (e.g. SF6) to inform whether and how these passive tracers may be useful in field trials (e.g., estimating rates of atmospheric CO2 uptake).

- Inform a prioritized set of predictions to be tested during field trials.

- van der Molen, J., Ruardij, P., Mooney, K., Kerrison, P., O’Connor, N.E., Gorman, E., Timmermans, K., Wright, S., Kelly, M., Hughes, A.D., Capuzzo, E., 2018. Modelling potential production of macroalgae farms in UK and Dutch coastal waters. Biogeosciences 15, 1123–1147. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-1123-2018

- Coastal Dynamics Laboratory, https://faculty.sites.uci.edu/davis/methodology/

Accelerate Design and Permitting of Controlled Field Trials

Proof-of-concept field trials are urgently needed to test both cultivation and sequestration technologies, as well as the full array of impacts. Field trials are needed to test predictions regarding:

- Cultivation yields and their dependence on species, ocean basin, nutrient availability, and farm design among others

- Performance of deep-water moorings

- Impacts to pelagic marine ecosystems

- Performance of harvesting technologies

- Additional CO2 uptake from the atmosphere into the macroalgae

- https://oceanvisions.org/our-programs/macroalgaeresearchframework/

Measure the Scale and Impacts of CDR via Macroalgae Sinking

Specific field experiments around the impacts of sinking seaweed in the deep ocean are urgently needed. Given the extensive amount of macroalgae cultivated and harvested in the coastal zone, we have more advanced knowledge of the scale impacts of natural accretion into sediments. We now need a global research effort around the fate and impacts of sinking seaweed in the deep ocean. To advance this agenda we need to convene scientists, engineers, seaweed farmers and more to:

- Identify existing deep-sea observatories, facilities, and vehicles to accelerate research on the fate of macroalgal carbon intentionally sunk in the deep ocean

- Develop a standardized list of biological indicators to measure during field trials to facilitate intercomparison between field trials

- Collaborate with existing farms to conduct field trials. This may be especially important for offshore farms that may be more representative of the open ocean conditions necessary to scale cultivation to achieve globally relevant CDR.

- Evaluate the potential to conduct sinking trials with portions of the supply of floating Sargassum patches to evaluate CDR and environmental impacts of sinking. Globally, there are ~10 gigatons of carbon in these Sargassum patches1, much of which is otherwise destined to end up on beaches, where it may become an environmental nuisance and will decompose, returning its carbon to the atmosphere. This may also serve as a way of generating public support for macroalgae CDR given the considerable social, economic, and environmental issues caused by Sargassum patches.

- Review oceanographic data from past cruises, coastal observing systems, and buoy data to acquire needed physical, chemical, and biological information to assess site potential for field experiments.

- Data from pilot studies investigating the effects of kelp on local mitigation of ocean acidification (e.g., in the state of Washington, USA) may also provide useful information on macroalgae growth rates/carbon sequestration rates, as well as environmental co-benefits and risks.

- Gouvêa LP, Assis J, Gurgel CFD, Serrão EA, Silveira TCL, Santos R, Duarte CM, Peres LMC, Carvalho VF, Batista M, Bastos E, Sissini MN, Horta PA. Golden carbon of Sargassum forests revealed as an opportunity for climate change mitigation. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Aug 10;729:138745. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138745. Epub 2020 Apr 17. Erratum in: Sci Total Environ. 2021 Apr 15;765:144696. PMID: 32498159.

Measure the Scale and Impacts of CDR via Macroalgae Sinking

Specific field experiments around the impacts of sinking seaweed in the deep ocean are urgently needed. (Visit the mCDR Field Trial Database for the latest information on current field experiments.) Given the extensive amount of macroalgae cultivated and harvested in the coastal zone, we have more advanced knowledge of the scale impacts of natural accretion into sediments. We now need a global research effort around the fate and impacts of sinking seaweed in the deep ocean. To advance this agenda we need to convene scientists, engineers, seaweed farmers, and more to:

- Identify existing deep-sea observatories, facilities, and vehicles to accelerate research on the fate of macroalgal carbon intentionally sunk in the deep ocean (See partnership between Ocean Networks Canada and Running Tide)

- Develop a standardized list of biological indicators to measure during field trials to facilitate intercomparison between field trials (See Verra's Seascape Carbon Initiative.)

- Collaborate with existing farms to conduct field trials. This may be especially important for offshore farms that may be more representative of the open ocean conditions necessary to scale cultivation to achieve globally relevant CDR.

- Evaluate the potential to conduct sinking trials with portions of the supply of floating Sargassum patches to evaluate CDR and environmental impacts of sinking. Globally, there are ~10 gigatons of carbon in these Sargassum patches1, much of which is otherwise destined to end up on beaches, where it may become an environmental nuisance and will decompose, returning its carbon to the atmosphere. This may also serve as a way of generating public support for macroalgae CDR given the considerable social, economic, and environmental issues caused by Sargassum patches.

- Review oceanographic data from past cruises, coastal observing systems, and buoy data to acquire needed physical, chemical, and biological information to assess site potential for field experiments.

- Data from pilot studies investigating the effects of kelp on local mitigation of ocean acidification (e.g., in the state of Washington, USA) may also provide useful information on macroalgae growth rates/carbon sequestration rates, as well as environmental co-benefits and risks.

- Gouvêa LP, Assis J, Gurgel CFD, Serrão EA, Silveira TCL, Santos R, Duarte CM, Peres LMC, Carvalho VF, Batista M, Bastos E, Sissini MN, Horta PA. Golden carbon of Sargassum forests revealed as an opportunity for climate change mitigation. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Aug 10;729:138745. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138745. Epub 2020 Apr 17. Erratum in: Sci Total Environ. 2021 Apr 15;765:144696. PMID: 32498159.

Develop New In-Water Tools for Autonomous CDR Operations

A new suite of durable, seagoing technologies are needed to support macroalgae CDR RD&D. Technology development needs include:

- The recently announced Ocean and Climate Innovation Accelerator (OCIA), a partnership between the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Analog Devices, Inc. aims to accelerate the development and deployment of ocean sensors and could serve as a model for accelerating sensor development in other places

Develop CDR Monitoring and Verification Protocols

Standardized methodologies from third parties to verify uptake of atmospheric CO2 resulting from macroalgae carbon sequestration will ultimately need to be developed to enable trading of carbon removal credits. Key first steps to support development of these protocols include:

- J -B E Thomas, M Sodré Ribeiro, J Potting, G Cervin, G M Nylund, J Olsson, E Albers, I Undeland, H Pavia, F Gröndahl, A comparative environmental life cycle assessment of hatchery, cultivation, and preservation of the kelp Saccharina latissima, ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2020;, fsaa112, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa112

Accelerate RD&D Through New Partnerships

Research, development, and demonstration of macroalgae CDR may be accelerated and strengthened by creating partnerships with key industries/sectors, including:

- Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (García et al., 2020): Integration with finfish and shellfish to leverage cost savings with operations and achieve permaculture-style benefits (macroalgae can take up waste products generated by fish; fish can feed on macroalgae, the increase in pH from the presence of algae can also be beneficial for shellfish whose growth is already threatened by ocean acidification).

- Offshore wind farms are often viewed as “dead space” for other marine spatial uses but could provide power sources and platforms for macroalgal farms

- Microalgae companies to adopt best practices for shore-based nursery facilities, such as nutrient and light need to optimize growth and facility design(s) that maximize growth potential and minimize cost.

Developing and strengthening relationships with partner industries may also help promote public support, as well as potentially offer faster routes to obtaining the necessary permits.

- García-Poza, S., Leandro, A., Cotas, C., Cotas, J., Marques, J.C., Pereira, L. and Gonçalves, A.M., 2020. The Evolution Road of Seaweed Aquaculture: Cultivation Technologies and the Industry 4.0. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), p.6528.

Broaden Funding Base for RD&D

Injection of significant funding is critical to move forward needed RD&D projects for CDR generally, for ocean-based CDR, and for macroalgae CDR specifically. In addition to national and subnational governmental support that is vitally needed and has been outlined in the Expanding Finance and Investment road map, additional stakeholders that need to be engaged include:

- O’Shea, T., Jones, R., Markham, A., Norell, E., Scott, J., Theuerkauf, S., and T. Waters. 2019. Towards a Blue Revolution: Catalyzing Private Investment in Sustainable Aquaculture Production Systems. The Nature Conservancy and Encourage Capital, Arlington, Virginia, USA.

- Sustainable Seaweed Solutions, www.ess.uci.edu/~sjdavis/seaweed.html.

Growing & Maintaining Public Support

First-Order Priorities to build public support for ocean-based CDR pathways are found in the Public Support road map, but there are some specific elements that can be emphasized to cultivate public support around macroalgae-based CDR:

These include:

- The perceived advantage of nature-based approaches for macroalgae pathways (Bertram & Merk, 2020)

- Identification and quantification of the co-benefits associated with macroalgae cultivation

- Inclusion of coastal blue carbon ecosystems as part of a campaign to build broad public support for macroalgae.

- Bertram C and Merk C (2020) Public Perceptions of Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal: The Nature-Engineering Divide? Front. Clim. 2:594194. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2020.594194

Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement

State of Technology

State of Technology

Overview

This document covers technologies designed to produce ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) from:

- Mining and distribution of natural rock-based alkaline minerals, including olivine and other silicate rocks as well as limestone and other carbonate minerals, either in open ocean (ocean liming) or coastal environments (coastal enhanced weathering) (Meysman & Montserrat, 2017; Renforth & Henderson, 2017; Lenton et al., 2018; Köhler et al., 2013; Köhler et al., 2010).

- Production of hydroxide minerals, including lime/slaked lime (Kheshgi, 1995) from thermal calcination and magnesium hydroxide from synthetic weathering of olivine (Scott et al., 2021) and distribution in the open ocean.

- Accelerated weathering of limestone (AWL) in ex-situ reactors to sequester non-fossil, point source CO2 emissions. Note that AWL requires a concentrated source of CO2 in seawater because carbonate minerals are oversaturated in seawater at ambient CO2 concentrations.

- Production and addition of hydrated carbonate minerals to seawater for increased alkalinity (Renforth et al., 2022)

In contrast to recent reports (Gagern et al., 2019; EFI, 2020; Rackley, 2020), we consider these four mineral-based pathways of OAE together because of the common upstream and downstream considerations necessary to accelerate the development and testing of OAE pathways.

We consider all electrochemical-based technologies for mCDR, including alkalinity enhancement, in a separate road map due to their separate set of upstream and downstream considerations for electrochemical processes.

We also do not consider enhanced rock weathering in terrestrial ecosystems here despite its similarities with coastal enhanced weathering and its potential for gigaton-scale CDR (Beerling et al., 2020). Enhanced rock weathering in agricultural fields presents its own set of obstacles and development needs, many of which are distinct from those of the marine pathways considered in these road maps.

- Meysman FJR, Montserrat F. (2017) Negative CO2 emissions via enhanced silicate weathering in coastal environments. Biol. Lett. 13: 20160905. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0905